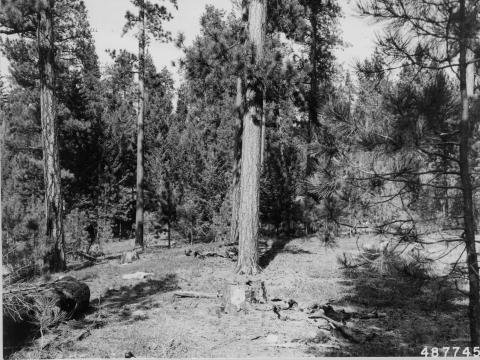

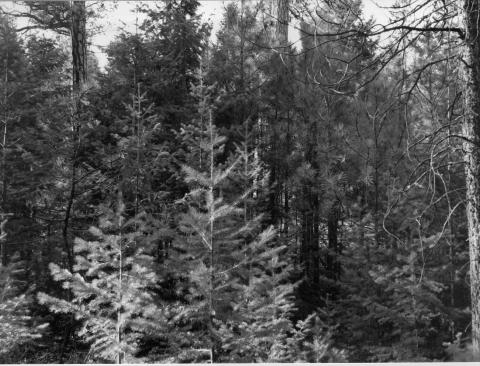

Living things change constantly, as do communities of living things. In a forest, where individual trees can live for centuries and new plants replace old plants, it is not easy to visualize the changes that occur over time. This photoseries documents changes in a ponderosa pine forest from 1909 to 2015.

Download high-resolution photos here.

See all years for each photopoint combined at the end of this Journal of Forestry article.

Details about "A Century of Change in a Ponderosa Pine Forest"

Before the First Photo: In the 1900s, this was an open forest of ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), typical of millions of acres of forest in the western United States. The forest contained scattered large trees and patches of young trees. Fires had burned through the grass and pine litter on the forest floor every seven years, on average, since before 1600. These fires had little impact on large trees but killed many of the young trees, although some survived. Records from the site tell us that the original forest had about 50 trees per acre and plenty of grass and lupine, an early summer wildflower that supplies nitrogen to the soil. Each time a fire burned through, it would kill the tops of the grasses and flowers, but they resprouted from underground stems, sometimes within weeks. There were few tall shrubs but many low-growing ones. Most of these also sprouted after each fire.